Animals Need Us to Be Rich

As we spend less of our income on food, improving agriculture becomes more affordable

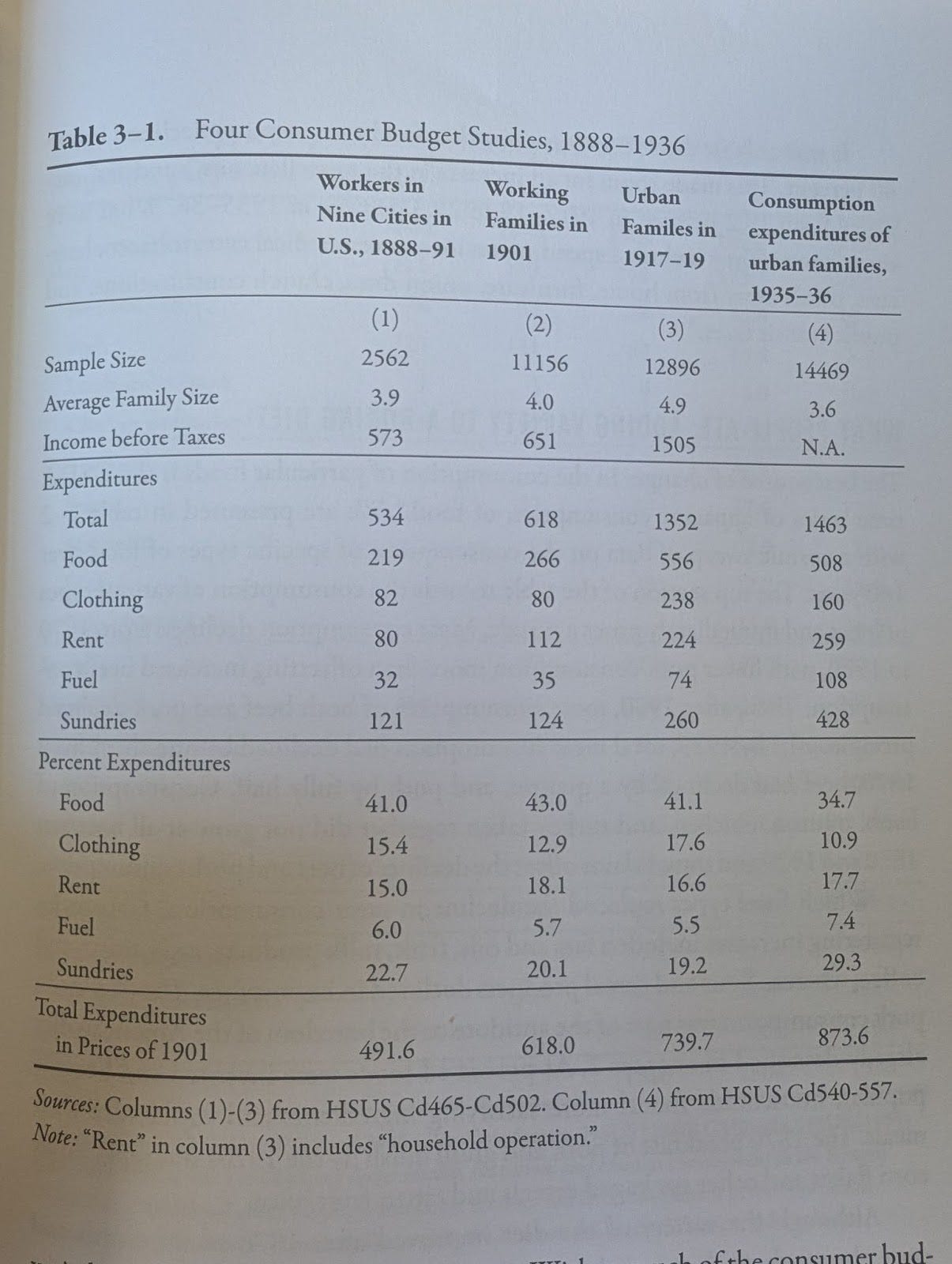

In historical terms, the way we raise farm animals today is strikingly new. The industrialization of animal agriculture only began after World War II, and in just eighty years it has completely transformed how we produce animal products. This transformation made food much more affordable: a century ago, the average American household spent 40% of their income on food. Today, that figure is just 10%.

As industrialization made food more affordable, people could begin considering not just whether they could afford to eat, but also how their food was produced. We can see this shift in the legal protections for farm animals that emerged, and in today's market for higher-welfare products that cost more but treat animals better. Now, as we look toward a future of potentially unprecedented wealth from advances in AI, we have an opportunity to take this even further: to build an agricultural system that truly reflects how we believe animals should be treated.

A short history of paying more for welfare

In the not-so-distant past, agriculture looked a lot different than it does today. As recently as the early 20th century, 40% of Americans lived on farms. These farms were much smaller than modern farms, and often involved a mix of different types of crops and livestock. Animal welfare was more an issue of how you and your neighbors treated the few animals that you directly interacted with, rather than how others treated animals on your behalf.

At this point, agriculture was significantly less efficient than it is today because farmers lacked economies of scale and technological capabilities. As a result, feeding a family could be extremely costly. It wasn’t uncommon for a household to spend 25% of their total income on food. While expensive by today’s standards, this itself was a massive improvement from early in history. For example, at the end of the 19th century, household food expenditures were over 40%.

Then, around the end of the second world war, things began to change. As part of the broader post-war transformation of the American economy, agriculture became larger, more mechanized, and more efficient. Farms began to specialize in particular types of crops or livestock, and they started to operate more like factories. The Green Revolution of the 1960s saw the introduction of genetic optimization, chemical pesticides, fertilizers, irrigation, and large machines that could automate many labor-intensive parts of farming.

For the average US citizen, this was a huge economic windfall. Average household expenditures on food fell rapidly during this period from 20% to below 15%

Around the 1950s, there started to be a growing awareness around farm animal welfare as a distinct social cause. Part of the reason for this was that husbandry practices were beginning to change in order to be compatible with large-scale industrial production models. For example, around this time it became common practice to keep laying hens in small cages so that their eggs were easy to harvest on a large scale. It was hard not to notice that the drive towards economic efficiency was sometimes at odds with humane treatment.

Another factor driving increased awareness of animal welfare was that fewer and fewer people were actually involved in the rearing of animals. Post-war urbanization and increasing per-farm efficiency meant that farming went from a ubiquitous part of life, to something other people did far away. On the one hand, this disconnected people from the conditions in which their food was produced. But on the other hand, it made it possible to talk about things like industry standard practice, and it shifted animal welfare from a matter of personal individual responsibility to one of collective concern and public policy.

A third factor increasing awareness was simply that growing societal wealth allowed people to start considering “nice-to-haves” like animal welfare. Animal welfare may be difficult to prioritize when food is scarce and you’re worried you might not have enough of it. However, once it becomes a guaranteed fact of life, things like welfare can increase in salience.

This growing awareness culminated in 1958 with the passage of the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act (HMSA), which to this day remains one of the only federal laws that explicitly regulates farm animal welfare. The law states that livestock (which was later interpreted to include cows and pigs, but not chickens) must be rendered unconscious and insensible to pain prior to slaughter. The public support for this commonsense regulation was massive. So much so that President Eisenhower at the time said "If I went by mail, I'd think no one was interested in anything but humane slaughter." Senator Richard L Neuberger said “today the national conscience is asking why we subject our animal friends to such cruel and inhumane treatment. These animals are not only our friends but the foundation of our abundant agricultural economy.”

Then in the 1980s, when food costs fell below 10% of household income, the market began to segment with higher-welfare products. Product attributes like "free-range" allowed consumers with disposable income to identify producers with practices more in line with their values, and allowed producers to be compensated for better practices. Third party certifications setting higher welfare standards than industry norms began emerging in the 80s and 90s .

Today, higher-welfare products have become a significant part of the American food landscape, especially in wealthier areas. Vital Farms, a company built on the promise of better welfare, has grown to become the second-largest egg brand in the country by revenue, and now accounts for around 3-4% of the total US layer flock. The broader egg industry has also seen dramatic shifts, with cage-free eggs now over 40% of US production, up from just 5% fifteen years ago.

In wealthy urban areas, the transformation is even more pronounced. Visit a Whole Foods in San Francisco or New York, and you'll find that animal welfare isn't just a premium option - it's built into their business model. Through programs like the Global Animal Partnership (GAP), every animal product on the shelf is kept to some baseline welfare standard. The meat counter features everything from basic no-crates-or-crowding chicken to pasture-raised grass-fed beef, and the dairy and egg sections offer similar tiered options for conscious consumers. The abundance of higher-welfare products in wealthier areas shows how prosperity has enabled our food system to evolve beyond commodity products driven purely by economic efficiency. The result is a system with more consumer choice, more options for companies to increase profitability, and better animal welfare overall.

Engel’s Law

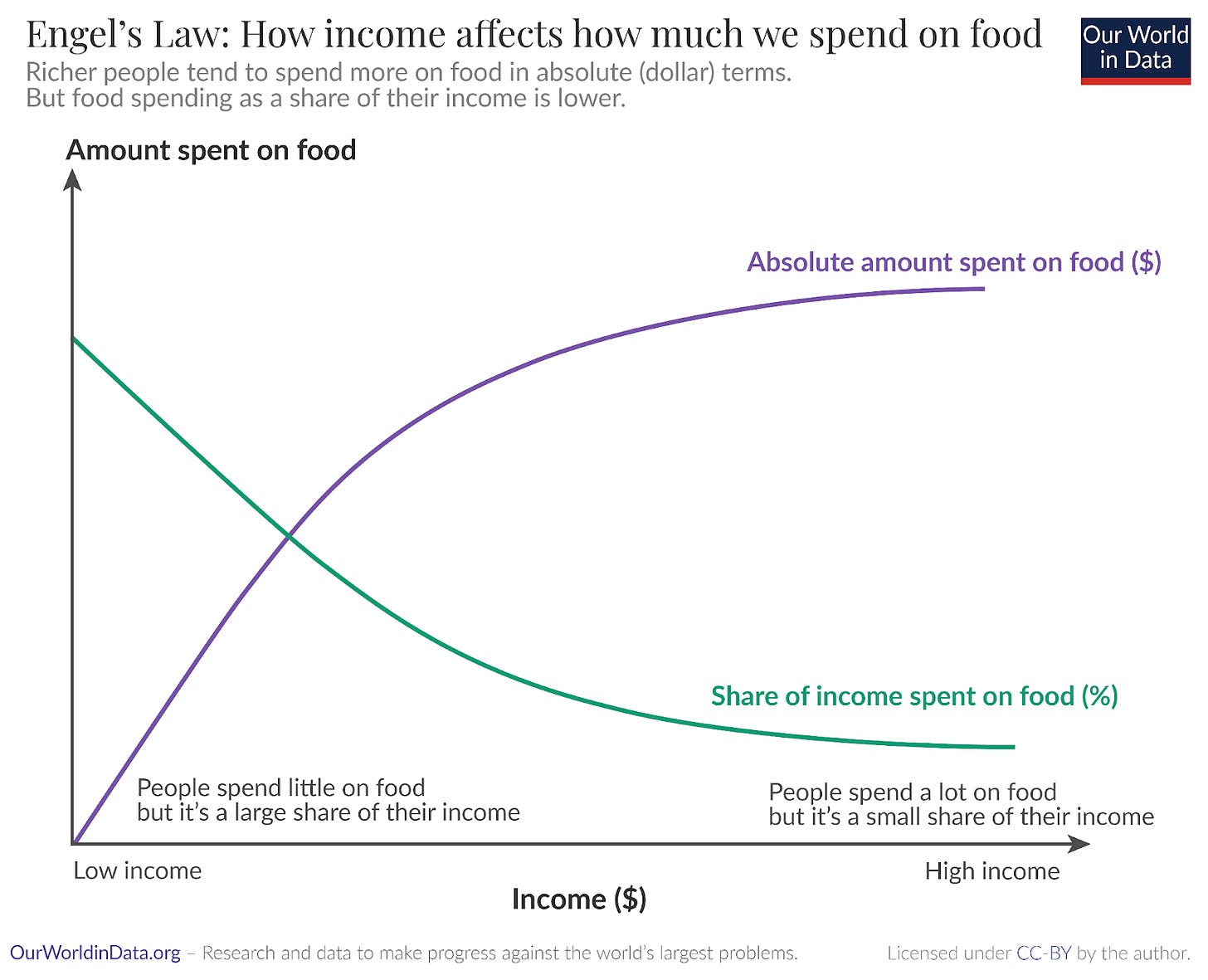

The overall trend we therefore see over the last 100 years is that as the wealth of Americans grew due to economic gains from industrialization, they spent a smaller percentage of their income on food. However, they also spent more on food in absolute terms. This is known as Engel’s Law, which states that as income grows, food expenditures fall as a percent of total expenditures, but absolute amount spent on food increases. Studies have shown that this is a universal trend, applying to a single country over time, to different populations within the same country, or even different countries at the same time.

Indeed, we can see this pattern playing out across countries today. Lower-income countries currently spend a higher percentage of their income on food than wealthier ones, while also spending less in absolute terms. Many of these countries are now going through their own agricultural industrialization, much like the US did in the mid-20th century. These countries may justifiably focus first on feeding their populations reliably and affordably, before turning their attention to things like animal welfare.

However, there's an important difference: developing countries don't have to completely recreate our path. They can learn from the experiences of other countries, and benefit from welfare-improving technologies already developed elsewhere. A new hatchery in Vietnam, for instance, can implement in-ovo sexing or other Hatchery of the Future technologies from the start rather than having to make a costly transition away from conventional methods later. This technological leapfrogging means that countries that industrialize later could achieve higher welfare standards than those that industrialized earlier.

Engel's law points to a theory of change by which we can gradually increase animal welfare over time. As societies get richer, two things happen: the absolute cost of welfare improvements goes down, and our ability to pay for them goes up. We know people have always cared about farm animals - the overwhelming support for the HMSA demonstrates this. Rising prosperity simply makes it easier to act on these longstanding values.

The path to better welfare will unfold in several ways. Some improvements will come through technology, which requires wealth to develop and deploy. Other improvements will emerge naturally from efficiency gains, like continued decreases in mortality. For challenges that represent true trade-offs with efficiency, like giving animals more space, we'll need to be rich enough as a society that the cost becomes trivial. And for these challenges where market forces alone aren't enough, government support could play a crucial role - but this too requires a prosperous society that can afford to subsidize better practices.

Affording our ethics

This theory of change helps underscore why the “degrowth” mindset is so counterproductive - it fundamentally misunderstands the role of wealth and growth in externality mitigation. Industrialization might have created some of the welfare challenges we face today, but it has also given us the economic foundation to solve them. Without this foundation of abundance, we'd be stuck choosing between feeding people and treating animals well. We need solutions that harness industrial capabilities while also steering them toward better outcomes.

Some believe that artificial intelligence will dramatically accelerate economic growth in the coming decades. It's hard to imagine how society might change as a result, but given such radical transformations, we shouldn’t confine ourselves to only thinking about welfare improvements that are currently feasible. In a significantly wealthier society, even the poorest parts may have food options that look like the San Francisco or New York of today. Eventually, we could afford practices that now seem to us like science fiction, such as AI-driven husbandry that can give top-notch individualized care to millions of individual animals at a time.

I’m not particularly rich compared to the wealthiest Americans, but my life is pretty great. All of my basic needs are easily met, I enjoy my work while having adequate leisure time, and there's little that money could buy that would meaningfully increase my happiness. Of course, everyone in the world deserves this quality of life, but I sometimes wonder how I would personally benefit from radically increased economic growth. What else could wealth buy that I don't already have?

This is the answer. Fundamentally, wealth represents the ability to sculpt the world into what we want it to be. An agricultural system that is both abundant and in line with our values is something we clearly want, but we don’t currently have. And only by being rich can we afford it.

Innovate Animal Ag, the think tank behind The Optimist’s Barn, is hiring! And if you read this newsletter, that’s a pretty good indicator of potentially being a fit. We’re not looking for folks with specific types of experience, we want exceptional people that are deeply passionate about our mission and theory of change.

To lean more, visit our Careers page.

Interesting take! I've historically been concerned that as developing countries get richer, things get worse for animals since people start buying more meat. But you're right that eventually people may get rich enough to pay extra for humanely-farmed products.

It seems like whether economic growth will be good for animals depends on:

1) How likely it is that developing countries ever get rich enough for humane farming

2) How long it takes them to get there

3) How good humane farming will be in this more abundant world (given it needs to make up for more meat consumption overall)

4) Whether plant-based eating grows faster than wealth does