The Gene-Editing Platform that Will Change How We Raise Chickens

A spotlight on NextHen's Layers Laying Broilers technology

Coming from Silicon Valley, where wild ambition is sometimes the price of being taken seriously, innovation in animal agriculture can sometimes feel stubbornly incremental. Plenty of new tools help animals stay healthier or make production more efficient, but true moonshots that have the potential to change the structure of the industry are few and far between.

One of the companies that bucks this trend is NextHen, a startup whose vision is to rethink how we do poultry breeding. Many of the challenges we’ve discussed on The Optimist’s Barn trace back to genetics. NextHen’s mission is to find practical ways to leverage better genetics to solve some of the biggest challenges the poultry industry faces around welfare, sustainability, and productivity. I sat down with Dr. Yuval Cinnamon, the CSO of NextHen and a Principal Investigator at the Volcani Institute, for a conversation about one of NextHen’s most exciting projects, called Layers Laying Broilers (LLB).

Growth vs. Reproduction

“Biology has a budget,” said Dr. Cinnamon during our conversation. “A human cannot both be a sprinter and also a sumo wrestler.” In other words, a biological organism that’s heavily optimized in one direction will start to perform worse in other areas.

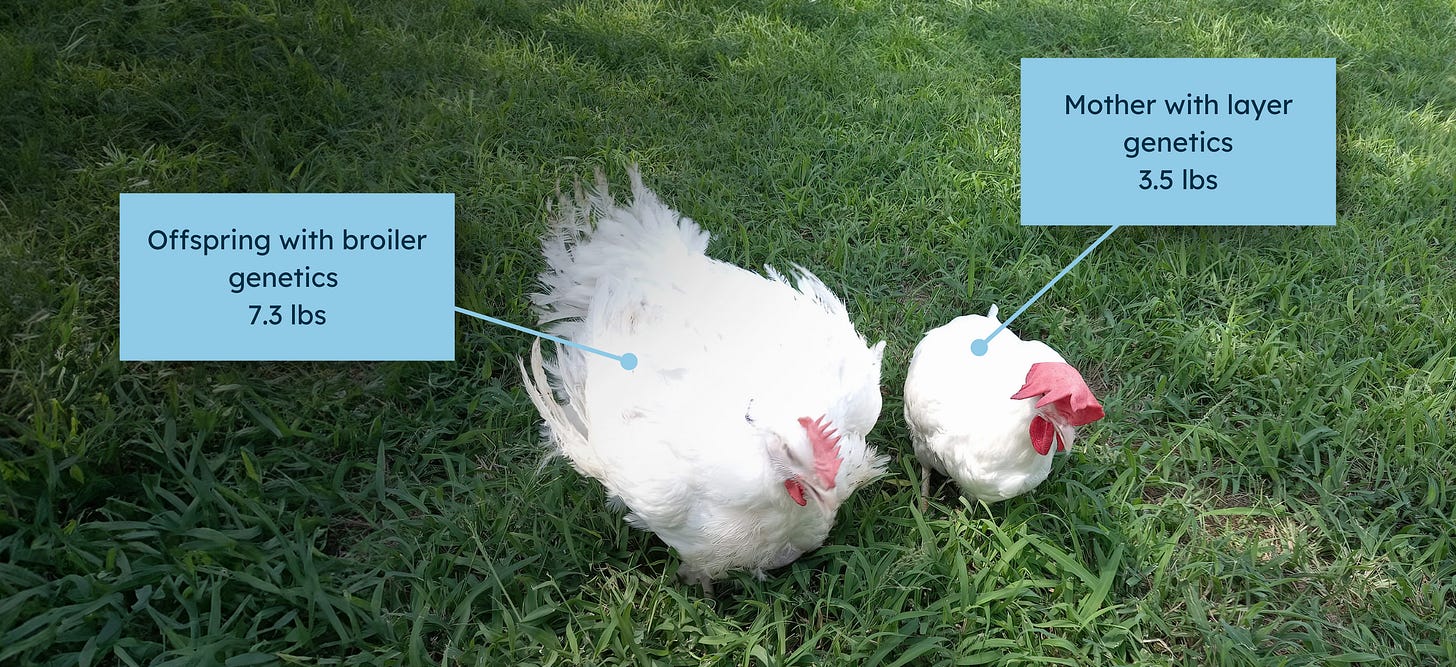

This is the situation for modern poultry. A century of selective breeding has pushed poultry into two specialized breeds: layers, optimized for egg production, and broilers, optimized for meat production. “The performance of the resulting breeds is clearly excellent,” he said, “but it comes with a price. And the price is that the fast growing broilers have very poor reproduction, and layers are excellent at laying eggs but they produce very little meat.” By his estimate, layers are 2.5 to 3 times better at producing eggs than broilers.

The challenge is that we cannot yet fully separate labor in the poultry industry into laying and growing–there still need to be chickens responsible for laying the broilers that are used for meat. These chickens, called broiler breeders, necessarily share genetics with the broilers. Broiler breeders are used for their reproduction, but have genetics optimized for fast growth.

This mismatch leads to a host of challenges for productivity, sustainability and welfare. “If broiler breeders had unlimited feed,” Dr. Cinnamon said, “they would grow so fast and become so heavy that they would not actually reach the age of sexual maturity. Imagine an average baby born at the weight of three kilos and growing to 200 kilos after two months. The metabolism of broiler breeders cannot adapt to this fast growth for too long. Their cardiovascular system will not support it. Their skeletal system will not support it. They will crash. And in order to prevent this, breeders must keep these parent stock under feed restriction from very early stages of development. And this is a major issue because for their entire life, they will be hungry. They were selected for many years to eat all the time, so their appetite is genetically endless.”

Hunger isn’t the only problem. Feed restriction often leads to elevated stress and aggression. Stress hormones in broiler breeds are measurably higher than in their layer counterparts, which are not kept under feed restriction. These hormones may also have maternal effects, meaning they can be transmitted to the offspring, causing the broilers themselves to be more stressed.

These welfare issues go hand-in-hand with lower productivity. A broiler breeder may lay around 140 eggs over its 60-64 week lifespan, while a layer can lay up to 400 eggs over its 100 week lifespan.

Until recently, these challenges with broilers breeders were a necessary part of poultry production, given the unbreakable genetic link between broilers and broiler breeders. But NextHen is seeking to change this with LLB.

Breaking the Genetic Link

At a high level, LLB uses gene-editing to create layers whose offspring can have distinct genetics from their own. These layers, called sterile surrogates, can then be used as the parents for fast growth broilers. In breaking the genetic link between broilers and broiler breeders, the LLB approach has the potential to completely solve all of the productivity and welfare issues associated with broiler breeders. It combines the best of a layer’s reproductive ability, and the broiler’s growth ability, fully completing the division of labor between the two breeds.

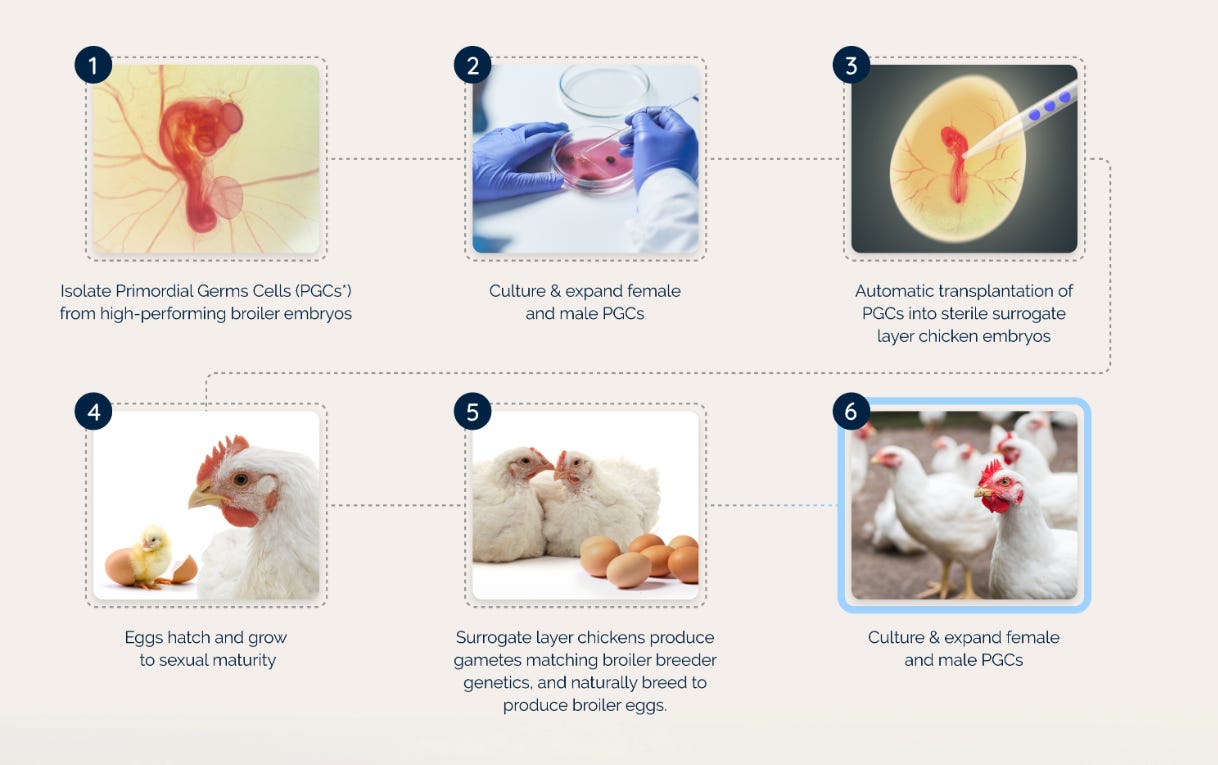

The process starts by isolating primordial germ cells (PGCs) from an existing fast growth broiler line. “The germ cells are precursor cells which give rise to the gametes, the sperm and eggs, and their only role in our body is to transfer the genetic material to the next generation,” explained Dr. Cinnamon. These germ cells are then cultured in-vitro and banked to ensure a stable supply.

Next, NextHen builds the surrogate layer line using a proprietary gene edit that confers inducible sterility, allowing breeders to control which birds become surrogates and which remain fertile to propagate the surrogate population.

When the surrogate layers are developing as embryos inside their eggs, the PGCs of the fast growth broiler line are transplanted into the eggs via an in-ovo process, like a more precise version of in-ovo vaccination. As the embryo develops, it treats the transplanted PGCs as it would its own native PGCs.

Once the eggs hatch and the surrogates grow up, they can be raised exactly like any other layer, except their offspring will be fast-growth broilers. These broilers can then be raised in exactly the same way that current broilers are. Although the sterile surrogate line is technically genetically modified, their offspring, the actual broilers, don’t share any of their surrogate parents’ genetics, meaning that the resulting meat can still be considered non-GMO.

NextHen has already successfully demonstrated this concept in a lab setting, and is in the process of developing the technology for commercial application.

The Future of Poultry

LLB is just one of the many projects in NextHen’s pipeline. For example, they also have an in-ovo sexing solution that can remove the need for male chick sorting and culling using similar gene editing techniques to LLB. Through clever breeding strategies, NextHen created a breed of layers named Golda with a gene edit only present on the male sex chromosomes. The gene edit allows hatcheries to selectively halt the development of male embryos (e.g. through exposure to blue light), so that only females hatch. Since the females lack the male sex chromosome which contains the gene edit, they can be treated as non-GMO.

NextHen is also exploring the potential of featherless birds. Feathers trap heat, driving up cooling and ventilation costs, and causing major welfare issues related to heat stress. Additionally, slaughter plants use significant water and energy for plucking. A viable featherless line could reduce heat stress while also lowering energy and water use.

It’s rare to see a company tackle the challenges of the poultry industry in such an innovative way. When I asked Dr. Cinnamon why he’s chosen to tackle these problems, he pointed to the long term importance of the chicken industry to the global food system. Given the superior feed efficiency and sustainability of chicken, Dr. Cinnamon anticipates the industry will continue to grow, especially in markets like India and Africa. “For the foreseeable future, I don’t see a replacement protein source that will replace animals. Animals have been used for food for thousands of years, and it’s a cultural thing. It’s not going to change very fast,” he said. “And until then, we need to raise these animals with compassion.”

This was not on my radar so it is interesting to learn about. I also appreciate Dr. Cinnamon, who has an amazing name for someone in the food industry btw, choosing to work on chicken welfare and his compassion for them. I'm sympathetic to NextGen's solution in principle, but I'm very skeptical that about the arguments that it won't be considered "non-gmo" based on the arguments given.

Consumer Adoption Skepticism (my half baked thoughts)

"Although the sterile surrogate line is technically genetically modified, their offspring, the actual broilers, don’t share any of their surrogate parents’ genetics, meaning that the resulting meat can still be considered non-GMO." I would love to hear the Non-GMO Project's opinion whether they considered it non-GMO, and assume they wouldn't be as generous.

I think the fears of rejection due to GMO are commonly somewhat overstated. Evidence of this is the vast amount of GMO-modified foods in Walmart where more Americans than not shop for groceries. So it is possible to produce GMO food and get consumer buy-in, though I believe this is a kind of passive buy-in. I could see that possible for NextGen given that is not directly GMO.

However, I become more skeptical when I remember AguAdvantage and what a failure that was from a consumer adoption point of view. 20 years to get regulatory approval, and then supermarkets drop them 3 years after they are approved to sell openly. So the GMOs in Walmart might be a bad comparative class since they are all plants and not meat, the GMO versions of the latter may have a greater likelihood of giving people the ick.

I become even more skeptical by how nerdy and in the weeds the distinction that needs to be made to not consider these chickens GMOs. I could easily imagine a future skeptical public saying something like, "It came out of a GMO chicken therefore it is GMO, duh," even though that is false.

From my pov, NextGen has already innovated in poultry genetics, but will need to the equivalent in GMO branding and PR, which they have not gestured towards, to be successful.

And as Dr. Cinnamon notes poultry is likely to grow in Africa and India as they become richer -- drastically growing number of farmed chickens. Those regions of the world are very anti-GMO -- see this article by the Genetic Literacy Project: https://geneticliteracyproject.org/gmo-faq/where-are-gmo-crops-and-animals-approved-and-banned/

So it seems unlikely to me NextGen will help with that problem, and will only be able to possibly help in the Americas, which is a still a huge region.

--

These just not my half baked thoughts and I could be missing something. If this kind of GMO-editing tech can be used in this way and be accepted by consumers, it would open up new welfare possibilities not just for farmed chickens, but other animals, like shrimp.

Thanks for sharing, fascinating