The Animal Welfare Premium is Not Captured by Certifiers, but AI Can Help

A value-chain analysis

PETA is up to some shenanigans again. Their target this time has been animal welfare certifiers and the advocacy organizations that support them, such as ASPCA, HSUS, and RSPCA.

They argue that animal welfare certifications lull consumers into a false sense of security, making them think products were produced humanely when, in fact, they were not. Their tactics include publishing critical newspaper ads and protesting outside the houses of the CEOs of these organizations.

Obviously, I’m against protesting outside the houses of the CEOs of these organizations.

But there’s a deeper reason why I think PETA is misguided. While certifiers do an admirable job at the difficult task of monitoring welfare on farms they don't control, the real issue is that third-party certification suffers from structural flaws that limit its influence on consumer behavior. PETA is protesting what is, in practice, a relatively minor factor in how consumers make decisions about animal welfare.

But that doesn’t mean animal welfare is irrelevant to consumer behavior. In today’s market it’s brands that consumers look to for assurances around animal welfare, not certifiers. To understand why this is, we first need to look at the economics of certification, and who is winning the welfare premium.

Why don’t certifiers do marketing?

Certifying organizations are all structured as nonprofits, but they can fundamentally be understood as businesses. Their business model is that they help farmers get paid more for better practices, then take a cut of the additional margin.

The more certifiers help farmers get paid, the bigger cut the certifier can take. This in turn depends on how much additional the consumer is willing to pay for the certification. From a business standpoint, the certifier’s ability to charge the producer is therefore a reflection of how much they drive consumer behavior.

But in practice, certification fees are surprisingly low, indicating that their influence on consumer purchasing decisions is limited. For example, Certified Humane, one of the main welfare certifiers in the US, charges 7 cents per case of 30 dozen eggs, or $0.0023 per dozen, and $0.001 - $0.003 per pound of chicken meat depending on the volume. Or, RSPCA Assured charges 5p per case of 30 dozen eggs, or 0.375% of the value of chicken meat sold (assuming a retail price of £2 per pound of chicken, this would be 0.75p per pound).

You might think that certifiers can’t charge very much because consumers don’t actually care much about welfare, but this is patently false. Setting aside any self-reported data, which consistently show consumers willing to pay substantial price premiums, you can look at the massive growth and size of specialty brands within animal agriculture. For example, Vital Farms charges around $6 per dozen eggs, around 4 times the national average. They’ve maintained these prices while being the second largest egg brand in the country by revenue, and while growing 30% per year.

Vital Farms’ brand means many things, but undoubtedly animal welfare is a critical piece of it. Their website and packaging prominently feature the welfare benefits of pasture-raised production, and their tagline is “Keeping it Bullsh*t Free,” touting exactly the kind of transparency that certifiers are supposed to provide.

Other brands like Whole Foods or ButcherBox are also commanding high premiums, in large part due to the assurances they can credibly provide around animal welfare. So welfare does drive consumer behavior, but the welfare premium is being captured by brands and not certifiers. That suggests that it’s brands that consumers look to and trust for assurance that animal were treated well.

This analysis may seem at odds with survey data. For example, a recent study of 1,000 US consumers by the ASPCA shows that a large majority (78%) believe there should be an objective third party checking on the welfare of animals on farms rather than just the company itself. There are two possible ways to understand this seeming inconsistency:

Certifiers are leaving vast amounts of value on the table by charging so little. This might be plausible since certifiers are nonprofits, not businesses, and they might not be squeezing every penny out of their customers like a ruthlessly profit-maximizing business would.

There’s a difference between the stated and revealed preferences regarding who consumers trust. Consumers might say they prefer third party certifications, but in reality they don’t look to the ones that exist, but rather individual companies and brands.

I generally think that certifiers could actually drive more animal welfare improvements by operating more like ruthless profit-maximizing businesses. Higher revenues would allow them to invest in better monitoring systems, build stronger brands that consumers trust, and create more compelling marketing that clearly communicates the value of welfare standards. The result would be more farmers adopting higher welfare practices and more consumers willing to pay for them.

However, I think the second explanation is more likely. Consumers are often confused by labels on animal products, and in my experience, it’s uncommon for consumers to have a strong sense of brand loyalty for any given certification. In other words, certifiers can’t charge very much because they don’t really drive consumer behavior.

What would Clay Christensen say

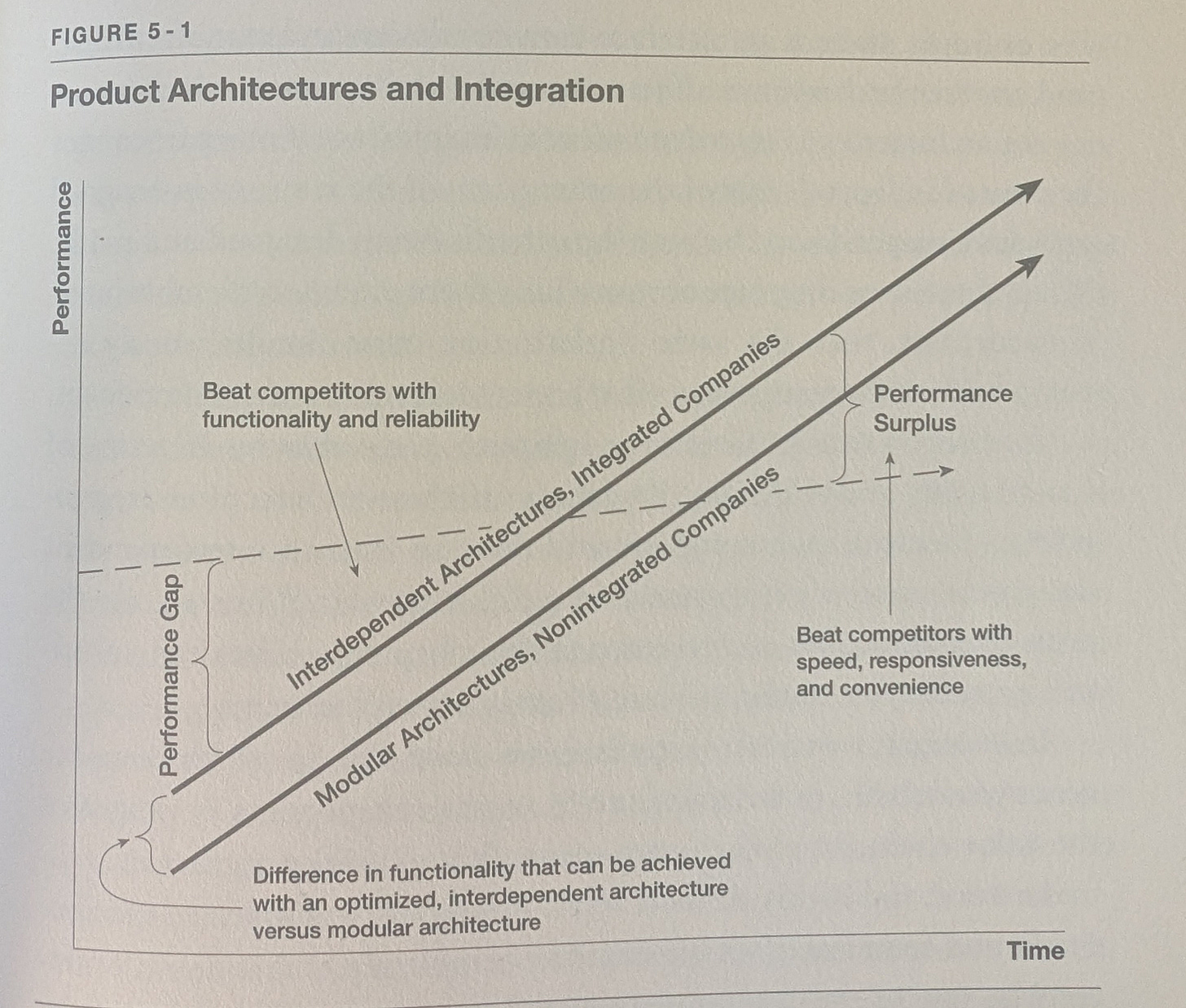

So why do consumers look to brands and not certifiers for assurance? Business theory gives one possible answer. In The Innovator’s Solution, Clay Christensen gives a theory of when industries tend to be vertically integrated (meaning individual firms control multiple parts of the supply chain) versus modular (meaning each part of the supply chain is controlled by a unique set of firms). What determines this structure is the overall performance of the sector: When performance is low and there’s a gap between what consumers want and what the supply chain can provide, an integrated company that can more effectively combine different parts of the supply chain will have an advantage. Whereas when products become “good enough” and there’s a performance surplus, then gains from specialization become more pronounced, and the value chain tends to be fractured into providers of individual components.

In the case of welfare certifications, we can think of the product the supply chain is trying to provide as trust. And what we see is a high amount of vertical integration between the parts of the supply chain that do farming, retailing, or marketing, and the parts that assure consumers that the animals were treated humanely. Certifiers do a fairly modular task - they define standards and provide assurances to consumers. Vital Farms does these things in addition to the farming, marketing, processing, packing, and distribution.

According to Christensen’s theory, the market is structured this way because there’s a fundamental performance gap in the supply chain’s ability to earn consumers’ trust. Put simply, people doubt welfare claims are legitimate. Vertically integrated companies can address that gap by controlling multiple parts of production—essentially saying, “Look, we own (or directly oversee) the whole process. Here’s the exact story of our chickens, our land, and our humane practices. We can name the farmers and show every step.” When trust is in short supply, these integrated operations deliver “higher performance” in providing credible welfare standards.

The aforementioned ASPCA study supports this theory: consumers were also asked how much they trust various parts of animal agriculture to treat animals well. Only around half of respondents reported having this trust, and likely this number would be lower for consumers looking for high welfare products. This suggests there is indeed a performance gap with trust in animal agriculture that vertically integrated producers are better suited to address.

Transparency, trust, and technology

If Clay Christensen’s analysis is right, then certifiers could become more successful in a business sense as overall trust and transparency in the supply chain improves. Once the gap between what consumers want (credible welfare assurances) and what the market can provide begins to shrink, the benefits of specialization become more compelling—even if that sometimes reduces efficiency. In such a scenario, the distinctive advantage for certifiers is their role as objective outsiders. Rather than producers declaring “We treat animals well—trust us,” an independent certifier could say, “We have no stake in this product’s sales; we only verify the welfare.” When consumers are generally ready to believe humane claims, they will want those claims to come from a neutral referee, not just from the producers themselves.

In the future, an emerging technology may hold the key to reaching this performance surplus: Precision Livestock Farming (PLF). PLF refers to a class of new technologies and approaches where sensors and monitoring equipment are used to gather large amounts of data on farms, which are then turned into business insights. While PLF is still in its early days and primarily focused on efficiency gains, its underlying monitoring infrastructure could, in theory, be repurposed to automate the process of welfare monitoring.

Right now, the way that certifiers actually monitor farms is fairly rudimentary. Producers must maintain extensive documentation on metrics relevant to welfare, such as disease events, ammonia levels, or mortality levels. Then, every 12-18 months, an independent auditor will come (announced ahead of time) to the farm. During this audit, they will review the documentation from the previous period to ensure that all of the requirements are being met, and they will also check attributes of the farm, such as making sure animals have access to outdoors, or that they have enrichment in the barn. If the farm passes this audit, they remain on the certification.

With PLF, one could imagine a certification where on-farm conditions are monitored 24/7 through cameras and other sensors, with AI analyzing the data to give a holistic welfare assessment. This kind of setup would be able to provide a much more robust sense of welfare than is possible now.

If this certification then succeeded in fixing the performance gap with trust, the farmer would stand to benefit substantially as well. A more powerful certification with strong brand recognition and trust would be able to drive significantly higher premiums from consumers, and the farmer would capture most of it. Instead of having to focus on piles of paperwork, they could get paid more for focusing on what they’re good at: animal husbandry.

Additionally, a stronger certification could allow farmers to be compensated for a wider range of better practices. With market incentives as they currently are, producers are pushed towards welfare improvements that can easily be explained and that are emotionally resonant with consumers. For example, it’s easy to describe what “cage-free” or “pasture-raised” means, and why people should care, allowing producers to command premiums for these practices. However, there are many practices that are harder to explain, or not as emotionally resonant, but which have substantial welfare benefits nonetheless (on-farm hatching being one example). Currently, there isn't a great way for producers to be compensated for practices like these. But with a trusted certification system, consumers could support better welfare practices even without understanding all the technical details.

In a future where every aspect of animal welfare can be continuously monitored and validated, certification could finally evolve into what consumers have always wanted it to be: an objective, data-driven guarantee of humane treatment. Not only would this give consumers more choice and autonomy over what they’re buying and enable new ways to improve animal welfare, it would also give farmers more ways to increase their revenue and margins. Such a shift would be an important step towards creating an abundant food system that’s beneficial for all stakeholders, and in line with our ethical values.

Innovate Animal Ag, the think tank behind The Optimist’s Barn, is hiring! And if you read this newsletter, that’s a pretty good indicator of potentially being a fit. We’re not looking for folks with specific types of experience, we want exceptional people that are deeply passionate about our mission and theory of change.

To lean more, visit our Careers page.