Don't Demonize Efficiency in Animal Agriculture

A review of We Are Eating the Earth, by Michael Grunwald

In Michael Grunwald’s new fantastic book, We Are Eating the Earth, he points out that “since World War II, the U.S. dairy herd has shrunk by two-thirds.” It’s true–in 1944, there were 25.6 million dairy cows and now there are 9.3 million. This is even more striking when you consider that in 1944 there were 138 million Americans and now there are 342 million.

How can this be? Is it because rates of lactose intolerance are rising, or because people started to realize that dairy is a land-intensive process that’s bad for the climate? Or is it a triumph of vegan advocacy that convinced people to consume less milk, and instead drink alternatives like soy, oat, and almond milk?

None of the above–it’s because the average output of a dairy cow increased from 4,572 lbs per cow to 24,178 lbs per cow. That increase came from decades of selective breeding, improved nutrition, better veterinary care, and more optimized farm management. When each cow produces five times as much milk, you need significantly fewer of them

Getting more with less is a central theme in We Are Eating the Earth, where Grunwald offers a sober, realistic, and insightful take on how we can feed a growing population in a world that’s heating up faster than we’d like. He zeroes in on how we tally the climate costs of agriculture, and how bad climate accounting has led us toward flashy but counterproductive solutions. When we do the accounting right, two truths emerge: first, there are no silver bullets in agriculture. Second, increasing productivity is one of our most powerful tools, because it lets us produce more food with less impact.

Focusing on the virtues of agricultural productivity may seem surprising coming from a staunch environmentalist like Grunwald. But it reflects a broader truth: industrial agriculture may cause emissions, pollution, and poor animal welfare, but the more efficient agriculture is, the less of it we need.

The Opportunity Cost of Land

When it comes to climate accounting, Grunwald argues that land use is often the most overlooked aspect. The reason conserving land is important isn’t just to preserve scenic vistas or to protect endangered species. It’s because forests, grasslands, and other natural ecosystems are the best ways we have to keep carbon in the ground rather than in the atmosphere. Converting land to other uses, even purportedly climate-friendly ones, always comes with opportunity costs that many carbon accounting models ignore.

Grunwald goes through much discussed climate solutions like ethanol, biodiesel, and biomass energy, and explains why each is either useless, or even potentially harmful if it requires land to be repurposed. For example, growing corn as a biofuel may be positive on a narrow accounting (because corn takes carbon only out of the air and top soil), but it’s actively harmful if you take into account the opportunity cost of the land on which the corn is grown.

Of course, we need to use some land to feed people. But the less we use, the better. And one of the best ways we have to use less land is to get as much as possible out of the land we do use. This is why solutions like regenerative agriculture also fail as climate solutions. They’re less efficient, require more inputs, and demand more acreage to produce the same amount of food.

To critics of industrialized agriculture, this analysis may be frustrating. They might argue that a ruthless drive towards efficiency is exactly what caused all these problems in the first place. But that perspective misses something crucial: it’s only because agriculture is so efficient that we can feed 8 billion people today without already having cut down the rest of the world’s forests.

To be sure, industrialized farms have a host of problems that smaller farms don’t, both for the climate and for animal welfare. But many of these issues aren’t intrinsic to efficiency itself; they’re unintended side effects of how efficiency has been pursued. The ruthless efficiency of industrial agriculture makes them hard to fix, but in theory, if we can solve them without sacrificing productivity, we can actually make things better.

Efficiency Saves Lives

If flawed accounting can mislead us about climate solutions, it’s worth asking whether we’ve also misunderstood the effects of industrialization on animal welfare. It’s easy to assume that efficiency always comes at the animals’ expense. But the data tells a more complicated story.

One key dynamic is that the more food each animal produces, the fewer animals we need to raise. We consumed roughly 498 pounds of beef per cow in 1960 versus 795 pounds today, 141 pounds of pork per pig in 1960 versus 173 pounds today, and 3.04 pounds of chicken meat per chicken in 1960 versus 4.08 pounds today.1

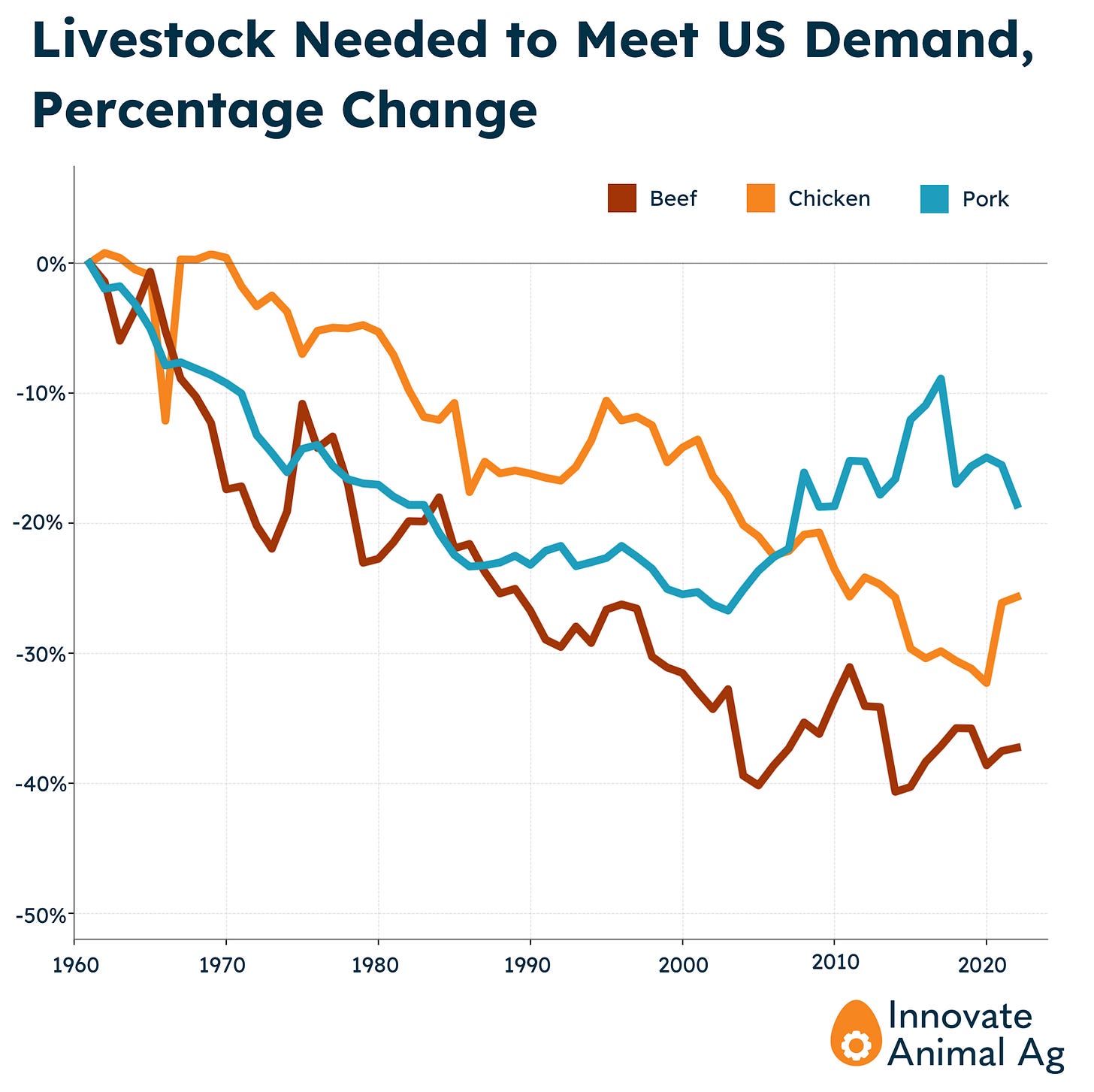

Of course, overall meat consumption and population levels have both risen, so outside of the dairy sector, the total number of animals hasn’t gone down. But it hasn’t gone up as much as you’d expect. To try to understand how much impact efficiency has had, we can try a simple counterfactual: What if we held today’s demand constant, but produced it using the efficiency levels of 1960?

Under this analysis, we see that increases in agricultural efficiency since 1960 mean that we need 20-40% fewer animals to meet current demand, depending on the species.2 Just in 2023, these efficiency gains would have accounted for 26 million fewer cows, 29 million fewer pigs, and 3.3 billion fewer chickens than would have been needed with the agriculture of 1960. On this method of accounting, efficiency gains have averted more animal deaths than any sort of climate or animal advocacy ever has.

Of course, that isn't the only way to do the welfare accounting. For one, efficiency also lowers costs, which can drive up demand. And comparing agriculture now to agriculture in the 1960s isn’t apples-to-apples. There are many health and welfare issues that animals face now that they didn’t in the past. For example, the increased size of the average chicken has led to painful heart and leg problems that were far less common in historical breeds.

At the same time, we also can’t necessarily claim that welfare is worse in every way now than it was in the past. One meaningful metric is “mortality”– the number of animals that die before reaching slaughter. In 1915, mortality for broilers was a whopping 18%. By 1960, it had dropped to 6%, and in 2012, it bottomed out at 3.7%. It’s since crept back up to 5.9%, for reasons that aren’t fully understood. These deaths usually result from painful conditions like disease, infection, or organ failure, so a lower mortality rate suggests that at least some aspects of welfare on the farm have improved.

To complicate matters even further, another welfare accounting method one might use is the amount of time chickens spend on farms. Thanks to faster growth, chickens now live much shorter lives before slaughter: 112 days in 1925, 63 in 1960, just 47 today. This means that we now only need half the chicken-days now to meet demand compared to how agriculture was in 1960. Whether you think shorter lives are a mercy or a loss depends on your ethical framework, but regardless, this is another kind of footprint that efficiency helps us shrink.

I’m not claiming right now that any one method of welfare accounting is the best one to use.3 But one of the lessons of We Are Eating the World, is that accounting methods really matter. And at the very least, we have to move past the overly simplistic heuristic that because industrial agriculture is both bad and efficient, efficiency itself must be harmful. Clearly, there’s more nuance here to understand.

It’s helpful to consider some specific examples of how efficiency affects welfare. Take male chick culling: in the egg industry, male chicks are routinely killed because they don’t lay eggs, and are too scrawny for meat production. This isn’t because culling itself increases efficiency, but because the industry became more efficient by optimizing separately for egg-laying versus meat production. That split made male chicks in the egg sector effectively useless, turning culling into an unintended side effect. The distinction matters since it means the problem is solvable if the solution doesn’t sacrifice efficiency. Technologies like in-ovo sexing, which identify the chick’s sex before hatching, offer a humane fix that aligns with the economic incentives.

Another example is the leg and heart issues in fast-growing broilers mentioned earlier. These problems also weren’t deliberately engineered–they emerged as unintended consequences of selecting for rapid growth and breast yield. Again, if broilers can be bred to have stronger hearts, or if we can change husbandry practices to improve the leg issues (such as through better vaccination methods), we may be able to solve these issues without sacrificing productivity. Some might worry that solving these issues would enable producers to push for even more efficiency, but as we’ve seen from this analysis, that might not be such a bad thing.

Silver-Bullets Fantasies

The final chapter of Grunwald’s book is called “How to Save the World.” One might expect from the title a clear roadmap of how to reform the food system to meet all of our climate goals. But then one would likely be left unsatisfied, which Grunwald acknowledges. Essentially the advice boils down to “try harder, do better, and don’t make things worse.”

But the unsatisfying-ness is kind of the point–the temptation to think that there was such a clear and easy road map often leads us into what Grunwald calls “silver-bullet fantasies.” In reality, agriculture is messy and always will be. We will always need to eat, and eating will always use land that could have been used to store carbon. The first step is to make sure we use that land as efficiently as possible.

But efficiency can only take us so far. Industrial agriculture has real challenges, and to solve them we need cost-effective, abundance-preserving solutions. In our pursuit of these solutions we need to be smart about how we measure the impact, as sloppy accounting can point us in useless or actively counterproductive directions. This work is complicated, controversial, and error-prone, but there’s no replacement for rolling up your sleeves and actually doing it.

Reading the book, I kept thinking about our agricultural system in relation to our healthcare system. Modern healthcare is immeasurably better than it used to be, but there are still diseases that ruin lives and cause immense suffering. But each year, things get better, and once we’ve cured one horrible disease, we move on to the next one. Modern medicine will never be “solved,” because there will always be ways that life could be better. But at any given point, we do our best to make it as good as possible.

Grunwald’s vision strikes me as adopting a similar ethic towards the planet, and I think it applies to animal welfare as well. There will always be ways to improve the lives of animals, and ways to be more efficient with the animals we do raise. We should continually push on both welfare and efficiency until we’re raising only as many animals as necessary, and giving each of them the best life we can, better than what they’d have in nature. And once we’ve done that, we should push even further. Animal welfare may never be solved, but we can always try harder, do better, and work not to make things worse.

Note that we’re talking about meat consumption here, not production, so these figures also take into account things like inedible parts of the animal and food waste.

The input into this model is the number of animals slaughtered per year. The conclusions would be even stronger if we took into account improvements in areas where animals die before making it to slaughter.

If you want to get extremely in the weeds with welfare accounting, I’d recommend checking out the Welfare Footprint Institute.

"To try to understand how much impact efficiency has had, we can try a simple counterfactual: What if we held today’s demand constant, but produced it using the efficiency levels of 1960?"

I do not think this is the right counterfactual. The demand for animal-based foods cannot be assumed to be constant because it is affected by the efficiency of animal farming. For the efficiency levels of 1960, animal-based foods would have remained way more expensive than now, and therefore the demand for them would have been much lower than now. Moreover, there would have been less population growth if the efficiency of all agriculture had remained at 1960 levels.

Agricultural land per capita has been decreasing (https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/agricultural-area-per-capita?country=~OWID_WRL), but this does not imply that greater agricultural efficiency tends to decrease cropland. Lower efficiency also tends to result in lower population growth, which contributes towards decreasing agricultural land. Furthermore, even if greater agricultural efficiency decreased not only agricultural land per capita, but also total agricultural land, it would still be the case that a lower efficiency of animal farming in particular would have implied less agricultural land holding the efficiency of the production of plant-based foods constant.

Total agricultural land increased a lot after the industrial revolution (https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/global-peak-agricultural-land?country=~OWID_WRL), so increases in efficiency have overall increased agricultural land. However, agricultural land seems to be now starting to decrease. I assume due to the continuation of increasing yields, and sufficiently slow population growth, and sufficiently slow growth of the consumption per capita of animal-based foods.

I have read Weighing animal welfare and dove deeply into the models. My review is 3 stars "at least they tried". The models give 10% credence to all animals having the same welfare range as humans. This is simply nonsense that drags up the mean. More weight is given to the behaviour vs neurophysiological model (60/30 IIRC) where the behaviour model is lacking a lot of data for these animals and the neurophysiological model destroys their p(sentience). I think assuming wild animals live net negative lives in ways where extinction is beneficial is extremely counterproductive and would advise against it given the uncertainty and benefits these animals often provide to the ecosystem.