DARPA for Chickens

How Innovate Animal Ag accelerates breakthrough technologies in animal agriculture

In 1957, the USSR launched Sputnik, seemingly vaulting ahead of the US in the space race. The stakes of this event extended far beyond demonstrating scientific prowess: the ability to reach space carried profound national security implications that compelled both superpowers to invest billions in research and development. What stung most for the United States was being caught completely unprepared.

The American response was to recommit to winning the space race, and to double down on investing in innovation. The following year, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) was founded with an explicit mission to prevent technological surprise and maintain American superiority. This new agency became a seemingly endless source of breakthrough innovations, contributing to pioneering research in the internet, GPS, modern semiconductor design, renewable energy, and machine learning. Competition, it turns out, breeds excellence.

The outsized productivity of DARPA as a hub of technological innovation is often partially attributed to its unique organizational structure. Rather than operating as a hierarchical bureaucracy like most government entities, DARPA functioned as a relatively loose federation of maverick inventors, innovators, engineers, and entrepreneurs, each granted significant autonomy and resources. The underlying HR thesis was to hire exceptional people and let them cook. By no accident, this philosophy would later become a cornerstone of Silicon Valley’s approach to talent.

DARPA’s success inspired numerous attempts to replicate its model. The US government created several spinoffs focused on domains beyond defense: ARPA-E for energy, IARPA for intelligence, and ARPA-H for health. Other countries followed suit, with the UK establishing ARIA and Europe launching JEDI. More recently, ARPA-inspired structures have caught hold outside of government, with organizations like Convergent Research, and Speculative Technologies.

ARPA is also foundational to Innovate Animal Ag, the organization I founded and currently run. Innovate Animal Ag exists to accelerate breakthrough innovation in animal agriculture, with a focus on animal health and welfare. Given this focus, we sometimes aspirationally refer to ourselves as the DARPA for chickens.

Organizations adopting ARPA-like models vary considerably in their implementation, so when I say Innovate Animal Ag is inspired by DARPA, here are some things I mean specifically:

We’re organized largely into discrete program verticals, each consisting of small teams with significant autonomy and accountability for success within their domain. These verticals operate mostly independently while still creating opportunities to share strategic lessons, networks, and expertise across the organization.

We focus on high-risk, high-reward breakthrough innovations rather than incremental improvements. This approach necessarily means some projects will fail, but we view that as a worthwhile cost of a hits-based strategy.

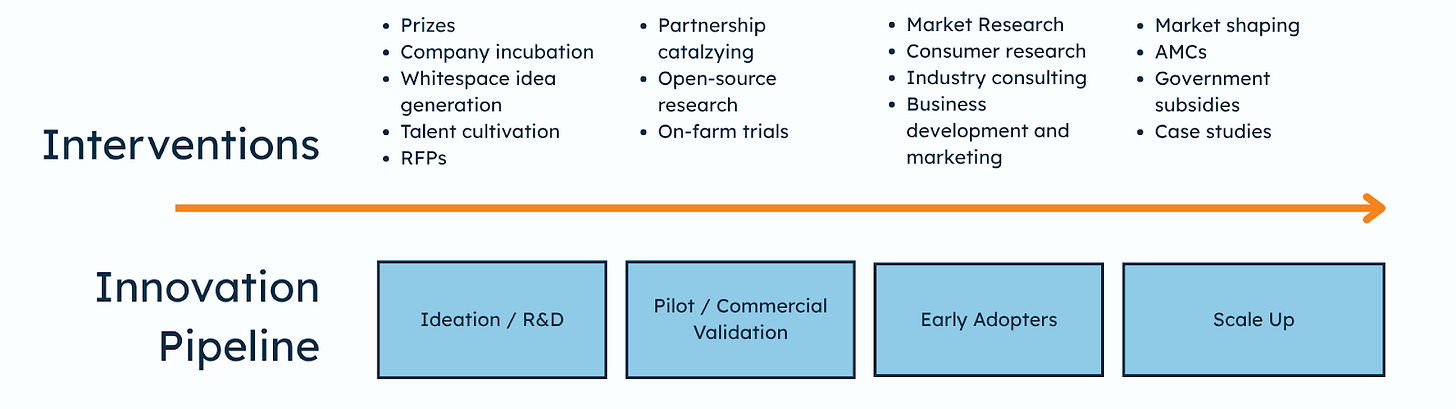

We’re intervention agnostic. Each innovation faces unique barriers depending on its stage of development and the specific challenges of its domain. Our process begins with rigorously identifying the bottlenecks for a particular technology, whether in R&D, commercial validation, regulatory approval, or industry awareness. After we’ve developed a hypothesis around this bottleneck, we then start to develop interventions to alleviate it. This might mean funding academic research, setting up commercial trials, publishing market research, or facilitating partnerships, depending on what the situation demands.

We have a strong emphasis on technology adoption, not just research. The most sophisticated technology means nothing if it never reaches the field, so we work hands-on with industry partners to understand concrete needs and accelerate real-world implementation.

ARPA-C

So how has Innovate Animal Ag put this model into practice within animal agriculture? Our first program area was in-ovo sexing, which we began working on in early 2023. At that point, we set an ambitious goal: bring this technology to the United States by the end of 2024.

The first step to making this happen was to deeply understand the current bottleneck of the technology. In-ovo sexing had already been successfully deployed in Europe, placing it in the “early adopter” stage of commercialization, yet it had not spread to other countries.

When we talked to egg companies in the US about the technology, we were surprised by what we heard: basically no one knew that the technology was already succeeding in Europe. This pointed to a clear bottleneck, since obviously no one would adopt the technology if they didn’t know it existed. And fortunately, it was a bottleneck that was relatively easy to alleviate. Over the course of 2023, we published research on the technology rollout in Europe as well as how American consumers were seeing the technology. We helped the poultry industry understand the technology through the trade press and by directly consulting with multiple egg companies in the U.S.

As far as getting companies to adopt the technology, in-ovo sexing was actually an incredibly easy sell, which is to the credit of the early adopters. NestFresh in particular is a brand I want to give a lot of credit to. They already believed that the challenge of chick culling was ethically important to solve, and they know the issue was deeply resonant with their consumers, so as soon as they understood the readiness of the technology they started to mobilize.

We worked closely with NestFresh over the course of 2024, and in December the first in-ovo sexing machine was installed in the US, meeting our initial goal just barely in time. The system became fully operational over the course of 2025, and the first eggs from in-ovo sexed hens reached shelves in July. The technology is now rolled out nationally, meaning American consumers now can purchase eggs from flocks where no male chick culling occurred.

After our initial success spreading in-ovo sexing to the US, we thought that it might be facing a similar bottleneck in other countries around the world. We ran the same playbook in Brazil in late 2023 and in Australia earlier this year. As a result, the first in-ovo sexing machine started operating in Brazil in July of 2025.

As in-ovo sexing gains traction in the United States and Brazil, the technology is transitioning from early adoption to scale-up. This shift means that the bottlenecks are changing as well, requiring us to adapt our strategy. We are currently developing interventions to accelerate scale-up until in-ovo sexing becomes standard practice worldwide.

Within the scope of possible interventions, this kind of market research and consulting perhaps wasn’t the most DARPA-y, but it was in the spirit of doing whatever most effectively unblocked technological progress. It was developing our subsequent program areas that brought us more closely in line with the traditional DARPA model.

The second technology where we invested heavily is electron beam (E-beam) inactivated bacterial vaccines. In 2012, the FDA restricted the use of antibiotics in animal agriculture as a measure to curb antibiotic-resistant bacteria. While this policy succeeded in reducing overall antibiotic use, it also left farmers with one fewer tool to combat bacterial infections in their flocks.

One of the biggest welfare issues for chickens that we use for meat is bacterial infections in their legs, which result from poor leg health due to their fast growth. Hundreds of millions of chickens die each year from a condition called “BCO lameness” before even being turned into meat.

E-beam technology offers a promising solution. Long used in food safety and medical sterilization, it has only recently become economically viable for animal health applications. E-beams kill bacteria by destroying their DNA while preserving surface proteins. These inactivated bacteria can then be injected directly into developing chicken embryos, where the preserved protein structures enable the chicken’s immune system to mount a robust protective response. This represents a significant advantage over traditional chemical inactivation methods, which destroy the bacterial cell structure and produce weaker immune responses.

Academic studies from the University of Arkansas have shown that E-beam inactivated bacterial vaccines can reduce BCO lameness by 50%, and there’s good reason to believe it will be even more effective with refinement. Most promisingly, vaccine doses could be manufactured at scale cheaply enough to have a strong ROI based on reducing pre-slaughter mortality for chicken producers. However, before Innovate Animal Ag got involved, the papers were gathering dust, and the technology remained stuck in the valley of death between proof of concept and commercial deployment.

Unlike in-ovo sexing, which needed awareness and early adopters, electron beam vaccines required commercial validation before industry adoption could occur. Our interventions reflected this different bottleneck. First, we partnered with the University of Arkansas to fund additional research into optimizing vaccine efficacy. Second, we are establishing commercial trials to test vaccine efficacy under real-world conditions with poultry producers, moving the technology one step closer to widespread adoption.

Looking Ahead

In-ovo sexing and electron beam inactivated bacterial vaccines represent our two largest program areas. Beyond these, we have also incubated a startup currently operating in stealth mode, where we identified a whitespace opportunity, developed the concept, recruited an external CEO, and helped secure initial funding.

We arrived at these focus areas through an extensive process of trial and error. Over the last few years, we explored numerous technologies including things like on-farm hatching, immunocastration for pigs, bird flu vaccination, percussive stunning for fish, and AI welfare monitoring. Some of these efforts failed to gain traction (remember, there will be some flops!). But often the process of failing deepened our understanding of the problem space, and suggested new ideas to trial in the future when we have more resources and capacity.

This learning process has positioned us well for expansion. We have a long list of ideas to try, plus direct experience accelerating innovations at three distinct stages of commercialization: early-stage research and development with our stealth startup, commercial validation with electron beam vaccines, and early adoption through scale-up with in-ovo sexing. With this experience and the DARPA model guiding our growth, expanding our portfolio of program areas will be our main focus in 2026.

As a nonprofit, nothing we accomplished in the past, nor that we’ll do in the future would be possible without the generous support of a large community of people who are involved in many different kinds of ways. If you are as excited about our growth as I am, there are a few different ways that you can support us:

We’re hiring for a Program Director role. This person will build and run new program verticals, functioning much like a DARPA Program Director. Being a regular reader of The Optimist’s Barn is definitely a positive signal for being a good fit for the role, so I strongly encourage readers here to apply. We’re offering a $2K referral bonus for a warm intro to a candidate we end up hiring, but we otherwise would not have met.

As we approach giving season, please consider making a contribution to support our work. Right now, the marginal dollar will go to hiring additional program roles, and directly funding technological development. Given how little is currently invested in innovation within animal agriculture, a small amount goes a long way. For example, typical research grants for top universities are often less than $100K, and recent cuts to federal research funding coming from USDA has made funding even more difficult to come by. Therefore, with fairly modest capital deployment, we can become the most important funder of livestock science research in the country, giving us tremendous ability to shape the research priorities of the industry towards addressing the most important welfare issues.

If you’re interested in giving, but want to first learn more about our program and room for more funding, feel free to reach out to me directly. As perennial believers in the power of aligning incentives, if a reader introduces us to a funder that we otherwise wouldn’t have met, we’ll offer a commission to the reader of 1% of the first-year donations from that funder.Finally, if you feel like you’ve gotten value from this Substack or its associated Podcast, please consider sharing with others who you think would benefit from it.

In my career, one thing I’ve learned about technological progress is that it doesn’t happen by default, especially in a sector like animal agriculture. Progress requires a community of dedicated evangelists and innovators who are obsessed with pushing forward the frontier. So thanks for being part of our community!